Introduction: The Origins of Antislavery in Birmingham

Transatlantic Slavery: A Historical Context

Aims for Learning

Introduction: The Origins

of Antislavery in Birmingham

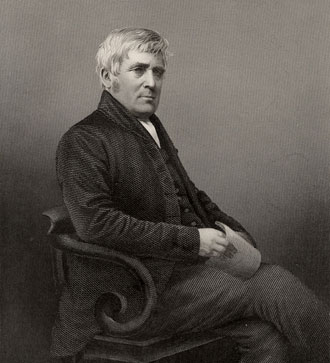

This is an engraving of Joseph Sturge (1793-1859), an important

figure in the history of Birmingham, who dedicated his life to bringing

about an end to transatlantic slavery in the nineteenth century.

Sturge started out in business as a ‘corn merchant’,

but was to spend much of his life pressing for urgent social change.

A devoutly religious Quaker, an educational reformer and advocate

of working class rights, Sturge contributed to many areas of Birmingham’s

public life. His most impassioned cause remained the abolition of

slavery around the world.

Responsible for oppressing millions of Africans for an unjust

profit, the transatlantic slave trade prospered in the late eighteenth

century. Birmingham itself, a town at the centre of the industrial

revolution, was far from untainted by this trade. Selling guns,

engines, metals and a range of industrial products, its growth became

linked to profits often made indirectly from the buying and selling

of slaves. For example, we know that a proslavery petition was sent

from Birmingham to Parliament in 1789 by those manufacturers who

feared that the economy of the area would collapse without the 'African

Trade'.

This situation did not go unchallenged. Through the dedicated efforts

of a wide range of people, Birmingham also became an important centre

of antislavery activity. The origins of its antislavery campaigning

can first be traced back to the 18th century, when the industrialists,

manufacturers, inventors and intellectuals of what became known

as the ‘Lunar

Society’ (which included members such as Matthew Boulton,

James Watt, Joseph Priestly, Erasmus Darwin and Josiah Wedgwood)

first regularly debated the problem. However, it was not until around

1825 that specific antislavery organisations were started in Birmingham.

Archives from this period help to us to remember and explore the

nature of campaigns by local men like Sturge, as well as the women

who established their own powerful antislavery society. In this

fight to establish a sense of social justice in the town, Birmingham’s

resistance to slavery went beyond being the product of one man,

one organisation, or one outlook. Many black abolitionists also

visited the town to deliver lectures. In this way, campaigning against

slavery drew in a shifting mosaic of people and tactics, leaving

a strong mark on the town’s history that should not be forgot.

"Joseph

Sturge Birmingham History Trail"

"Exhibition

on Birmingham's Industrial link to the Slave Trade"

<return to top>

Transatlantic Slavery: A Historical

Context

Slaves were men, women and children wrongly stolen by European

traders from family and society and transported from Africa and

other continents as cargo on terrifying journeys (the ‘middle

passage’) across the Atlantic. It was an ordeal which huge

numbers did not survive. Those who did were destined for the Americas

or West Indies where they would spend the rest of their lives as

domestic servants or plantation labourers. As the ‘property’

of their owners, they were allowed no legal rights or cultural identity.

Many slaves rebelled at the harsh conditions, led rebellions, formed

secret gatherings and subverted their master’s authority.

From as early as 1500 until as late as 1880s, a transatlantic slave

trade continued to exert itself as an unprecedented form of global

oppression. In Britain, the first ‘Society for the Abolition

of the Slave Trade’ was formed by William Wilberforce in 1787.

By the nineteenth century, many other antislavery societies had

spread across the country, very often meeting with strong resistance

from those who believed slavery was still necessary for trade. As

a consequence, antislavery laws were only gradually introduced over

a long period of time as a result of prolonged resistance.

A landmark was reached in 1807 when the first ‘Abolition

of the Slave Trade Act’ was passed. After this time, the actual

sale of slaves in the British Colonies was illegal. However, the

use of existing slaves would still be allowed until 1834, when another

act came into effect which ended the legal right to own slaves.

Even then, a corrupt ‘apprenticeship’ system was still

enforced in the West Indies until a further emancipation date of

August 1st, 1838. Meanwhile, slavery in America continued until

President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

Slavery in Cuba was legal until as late as 1886.

It is also important to remember that during the history of these

long and bloody struggles, it was not only Africans who were affected.

As slavery became legally abolished, unjust forms of cheap manual

labour became widespread. Wage slavery drastically affected the

Asian continent and displaced many communities. As 2007 marks the

bicentenary of the 1807 act, it is important to remember that since

then, many forms of illegal slavery have continued to operate around

the world. We still face the challenge of resisting the legacy of

racism, poverty and oppression deeply rooted in the history of the

slave trade. The work of the nineteenth century activists is unfinished.

<return to top>

Aims for Learning

This guide to antislavery in Birmingham has several interconnected aims: (1) to show images and arguments that act as creative starting points in provoking your own personal ideas and research into a subject often surrounded by silence. (2) to illustrate how local archives can help you navigate an ongoing journey between the present and the past. (3) to open a discussion on how early antislavery activists might be linked to later human rights activities within Birmingham. (4) to suggest directions for further study.

<return to top>

Image Reference: Local Studies and History: Birmingham

Portraits Collection.

Author: Dr Andrew Green

|