Background

Abolitionist Interactions

Birmingham: The Land of Freedom?

Directions for Learning

Background

In the 18th and 19th century, antislavery debate in

Birmingham could be heard from people of different racial origins

and class backgrounds. The important history of black antislavery

activists in the area can first be traced back to the visit of Olaudah

Equiano in 1790, who came to sell copies of 'The

Interesting Narrative' which told the story of his personal

escape from slavery, his life in the navy, business ventures, religious

conversions and development as an author. However, the history of

other black antislavery activists in Birmingham has only just started

to be recovered.

Whilst local abolitionist groups such as the 'Birmingham Anti-Slavery

Society', or the 'Ladies' Negro's Friend Society' inevitably remained

white middle class organizations, it is important to remember that

it would be Africans, West Indians and African-Americans who first

led the resistance against their own enslavement. It was their voices

that provided first hand evidence against slavery; it was their

physical, intellectual and creative spark of rebellion that lit

the fuse of the most striking campaigns. Black mutinies and uprising

were frequent.

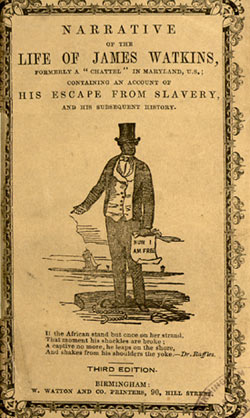

Black activists who came into contact with Birmingham gave dramatic

accounts of their experiences and often sold copies of autobiographical

'slave narratives'. In this context, Olaudah Equiano, Frederick

Douglass, Moses Roper, William Wells Brown, Henry Highland Garnet,

Samuel Ringgold Ward, J.W.C. Pennington, Alexander Crummell, James

Watkins and the Rev. Peter Stanford all made a connection with Birmingham

and its surrounding areas, and influenced local views on slavery.

Other names may yet be discovered.

For more information on Frederick Douglass and James Watkins,

click on the two right hand icons. For a short exhibition on other

black abolitionists with connections to Birmingham, click here:

Black

Abolition in Birmingham

<return to top>

Abolitionist Interactions

Black activists pursuing antislavery agendas arrived Birmingham

for a variety of reasons. In 19th century America, a 'Fugitive

Slave Law' meant that nowhere was safe for an escaped slave. Slave-catchers

could be legally employed to return the 'human property' to his

or her owner in the South. Faced with this crisis, many slaves fled

to Britain, where industrial towns like Birmingham might offer work

and refuge.

Not all 'fugitive' slaves were illiterate. Some were well-educated

antislavery speakers, lecturers and authors, intent on promoting

radical ideas of freedom among local audiences. Some black people

may have already 'bought' their own freedom. Others were religious

leaders, who communicated with local churches. Other may simply

have sought work as labourers: ex-slaves who arrived in Birmingham

alongside the great cosmopolitan influx of people from all around

the globe, a trend that allowed the town’s development into

a major site of labour and industry from the mid 18th century

onwards.

If most of the 'fugitives' or 'activists' would visit Birmingham

termporarily, it is likely that some probably ended up settling

in the area. Yet while partial accounts of a small number of ex-slaves

in Birmingham exist in their 'slave narratives', the majority were

unable to leave a record. We can often only reconstruct such stories

from fragments. Nevertheless, the current picture we have of the

relationship between black and white antislavery campaigners in

Birmingham is characterised by a range of experiences: co-operation,

argument, disagreement and, ultimately, a sense of shared struggle

in the fight to end the so-called gentlemen’s trade.

For example, the local abolitionist Joseph Sturge saw it as vital

to gain information and to practically support those that had experienced

slavery first hand. On his visit to the West Indies in 1837, Sturge

provided funds to emancipate a young black labourer named James

Williams; he also helped him to publish ‘A Narrative of Events

since the First of August, 1834, by James Williams, An Apprenticed

Labourer in Jamaica’. Yet the relationship between many ex-slaves

and white abolitionists appear not to have been easy; and whether

or not Williams ever visited Birmingham, we do not yet know.

We do know with more certainty about other black activists who

came into contact with Birmingham in the nineteenth century (a town

known for production of goods that were often used in the slave

trade). A good example of this is the case of the African-American

orator and intellectual Frederick Douglass who visited Birmingham

in 1846; or James Watkins, who came to Birmingham in 1852. You will

find more details on their lives in the following pages.

<return to top>

Birmingham: The Land

of Freedom?

After the emancipation acts of 1807, 1833 and 1838, England seemed

to promise a new home of liberty for those who still remained slaves

in America and the West Indies. In reality, those who did manage

to make the perilous escape to England away from their plantations

or owners faced new problems. It is certain that the ex-slave, black

immigrant and abolitionist alike did not always find it to be the

‘land of freedom’ they might have imagined (see the

story of John

Thompson, for example). Once here, they would still have experienced

racism and danger. In this, black ex-slaves confronted social barriers

that also affected the town's early Irish and Jewish communities.

At the same time, Birmingham’s history of nonconformist ideas

meant it was often sensitive to the stories of black experience;

and the rise of mid-nineteenth century interest in 'abolition' meant

that black speakers could often find a willing audience. Birmingham

had already been drawing in different people from around the world

in search of a chance to work and settle. It was a town of religious

diversity. It was the town of the entrepreneur. From the 18th

to the 19th century, its culture changed and diversified.

For example, from the ex-slave ‘jubilee singers’ in

1874, to Paul Robeson in 1949, many black

musicians would appear here to great popular acclaim.

Set against this rapidly tranforming backdrop, the complicated

and still emerging details of the lives of black slaves in Britain

and Birmingham suggests they were not here merely as passive victims

of great historical injustice, but as powerful agents of their own

fortune, vital sources of activism in the global struggle for social

justice, campaigners, artists and workers who vitally contributed

to British culture and political freedoms. They are a crucial, and

often overlooked, part of Birmingham's story.

<return to top>

Directions for Learning

Starting points for further discussion, or your own archive research, might include:

Why is so little evidence left of black antislavery campaigning in Birmingham, and how can we find new ways of using archives and other sources to recover their lost histories?

How does the work of these 19th century black activists anticipate later 20th century campaigns by people and communities from a wide range of racial and ethnic backgrounds in Birmingham?

<return to top>

Image Reference:

Local Studies and History: 'The James Watkins Narrative', Aston

X, 310, Birmngham Vol 26.

|