The Birmingham Anti-Slavery Society

The Men’s Campaigns

Later Histories and Connections

Directions for Learning

The Birmingham Anti-Slavery Society

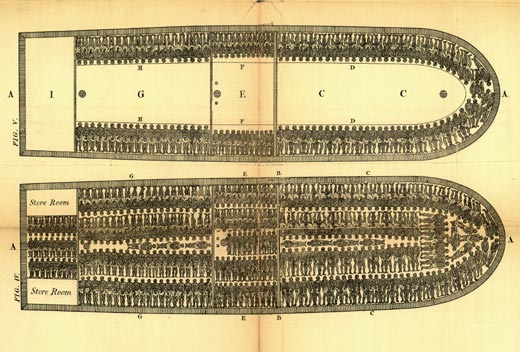

Images of African slave trade vessels inhumanly over-crowded with

people destined for plantations in America, the West Indies, Cuba

and Brazil provoked moral outrage in Birmingham. Formed 1826 in

resistance to the traffic in human beings, the 'Birmingham Anti-Slavery

Society' became a local, national and international campaign group

which took an important role in petitioning for nineteenth century

antislavery laws.

Joseph Sturge was a key member of the group, serving throughout

his life as one of its most impassioned leaders. Other members were

men of predominantly middle class backgrounds belonging to various

professions, churches, businesses, civic societies, town improvement

boards and medical professions. These included people such as Richard

Cadbury (the chocolate maker), Charles Lloyd (an important banker),

Rev. John Angel James (of Carrs Lane Church), Rev. Thomas Swan (of

Canon Street Chapel) and William Morgan (later Birmingham’s

Town Clerk).

The 'Birmingham Anti-Slavery Society' was dependant upon private

and public donations to survive, which meant it drew people of great

personal commitment to the cause, able to donate time, money and

effort outside of their own personal and working lives. Many of

its members were also involved with other reform societies, such

as ‘The Complete Suffrage Union’ (where Sturge backed

working class rights) and the ‘Baptist Missionary Society’

(promoting religious education in the colonies).

After the emancipation of the West Indies in 1838, the society

would became known as the Birmingham branch of the ‘British

and Foreign Anti Slavery Society’. This new name signified

a change of focus. Once slavery had been abolished in the British

Colonies, the Birmingham society now sought to combat the ongoing

existence of slavery in other nations, especially in America.

<return to top>

The Men’s Campaigns

The society grew from a relatively small local organisation in

1826 to play a major role in antislavery politics. It became particularly

renown for its role in calling for the end of the West Indies ‘apprenticeship’

system in 1837/38. At this time, being an ‘apprentice’

meant being a slave in all except name. To prove this point, Sturge

went on an extraordinary personal journey on behalf of the 'Birmingham

Anti-Slavery Society' to visit the area and uncover first hand evidence

for the true conditions of the people. His book A Visit to the West

Indies in 1837 is evidence of Birmingham’s central involvement

in bringing about the August 1st 1838 Emancipation Act.

Throughout its history, the 'Birmingham Anti-Slavery Society' established

cultural and political connections that drew Birmingham into contact

with activists and campaigners for social justice from around the

world. Two important examples of these contacts include Frederick

Douglass, the inspiring black intellectual who had personally escaped

slavery, and Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of the celebrated antislavery

novel 'Uncle Tom’s Cabin'. Having visited the West Indies

in 1837, Sturge was also no stranger to America. He later crossed

the Atlantic once again to write another antislavery travel narrative

entitled, 'A Visit to the United States in 1841'.

The overall outlook of Sturge’s antislavery society reflected

a mixture of radical possibilities set within conservative limitations.

It could be argued that some of the society may have acted more

from a belief that white civilized society needed to be freed from

the ‘sin’ of slavery, rather than from a sense of equality

with the African slave. At the same time, their expressed belief

in a ‘universal brotherhood of man’ threatened traditional

ideas about society, race and class. Spreading this belief in a

town which had profited from the ‘African trade’ was

an uphill battle; and their unorthodox views of religion often meant

the campaigners were dismissed as idealistic. For black abolitionists

who had experienced the horrors of slavery, however, they were never

quite radical enough.

<return to top>

Later Histories and Connections

Once slavery had been abolished both in the British Colonies (1838)

and in America (1863), the Birmingham British and Foreign Antislavery

Society had to adapt to new circumstances in order to support those

that were still left at risk. Joseph Sturge passed away in 1859,

ending an important chapter in Birmingham’s history. Without

him, a number of new socities formed.

In 1864 a ‘Birmingham Freedmen’s Aid Society’

was active. This began to send donations of tools and practical

materials to the American South to help black people suffering from

poverty in the post-emancipation period to reconstruct their lives.

Even as late as 1873, the evidence shows that people from Birmingham

maintained a strong interest in helping the oppressed slave. A meeting

in the town hall was held, January 22nd, 1873, “To promote

the Suppression of Slave and Man Traffic in Africa and Polynesia,

and the Abolition of Slavery in Cuba”.

Birmingham’s antislavery societies were also an important

forefather of ‘Anti Slavery International’, the campaign

group still in operation today, combating contemporary issues such

as wage slavery, illegal child labour and discrimination against

women. It is, in many ways, a close descendent of those first societies

led by Sturge and others. An account of this connection can be found

on the home page of www.antislavery.org.

<return to top>

Directions for Learning

Starting points for further discussion, or your own archive research, might include:

How effectively did antislavery activists in Birmingham engage with people of different races and cultures?

How might the attempt of Joseph Sturge and The Birmingham Anti-Slavery Society to combat oppression be linked

to later anti-racist campaign groups in Birmingham, such as The Indian Workers Association?

<return to top>

Image Reference:

Local Studies and History: Slavery Pamphlet Coll. A326.08 Volume

E/1 (facsimile plate).

|