The IWA and Employment

Discrimination in the Workplace

The IWA and the Unions

Self-Organising and Supporting Workers

Directions for Learning

The IWA and Employment

It was in the workplace, particularly in the foundries and factories of the Midlands, that the IWA made a significant contribution to struggles for social justice. Due to its rooting in Marxist and Leninist thought, fighting for the rights of working people was as important for the IWA as anti-racism. In its commitment to unionisation and to the dismantling of barriers which oppressed black workers, the organisation brought about empowerment to individuals through collective action.

<return to top>

Discrimination in the Workplace

Upon arriving in Britain in the 1950s and '60s, many Commonwealth migrants found themselves in low-paid, often hazardous, labour intensive industrial and service sector jobs. These were jobs in the expanding transport, service and industrial sectors which local people did not wish to perform. As a result, black workers were subject to both instability and a lack of recognition for the skills and qualifications they had brought with them to Britain. For migrant workers many inequalities existed in the workplace: they experienced discrimination in the allocation of tasks, pay and conditions, the provision of facilities and selections for promotion or redundancy. In the foundries where many black workers found work, it was not uncommon for Indian workers to pay 'entry money' to gain work, keep their jobs or perform overtime. The grim fact of discrimination was noted by Jouhl in his first job at Shotton Brothers in Oldbury where he found a clear division of labour along ethnic lines:

"All labourers migrant labour, all so-called skilled worker or moulders white all core makers white all fitters white all electricians white all operators white all dressers white so it was clear cut division low pay hard work migrant labour…"

<return to top>

The IWA and the Unions

The Indian Workers Association recognised that inequalities could be remedied through unionisation. By joining unions, Indian workers could find a voice with which they could assert their rights. Tackling the double oppression facing black workers as a result of being both black and working-class was a primary concern of the IWA. Members actively recruited other Indians workers first of all to the Amalgamated Union of Foundry Workers (AUFW) and then to the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU.) By demonstrating that victories against unfair work practices could be gained through collective protest, the IWA made union membership popular amongst Indian workers and gained its reputation for facilitating industrial struggles.

As well as campaigning against management practices, the IWA found that the unions also presented barriers that needed to be dismantled. Despite claiming that workers were united in the struggle against class oppression, unions themselves instigated exclusionary practices against migrant workers. Racism was rife amongst union members: in London, a strike and marches by the Smithfield meat porters and the Tilbury dockers in support of Enoch Powell in 1968 demonstrated that many union members were hostile towards immigration which prevented them from standing in unity with their fellow black workers. The dispute at Coneygre provides a significant example of the failure of unions at the time to support struggles of black workers. The AUFW notoriously condoned strike breaking by white workers instead of encouraging them to support fellow union members. As a result of this, confidence in unions plummeted and there were instances where Indian workers burned their membership cards on bonfires because of their betrayal by the unions. Black workers could not afford to wait for white workers to defend their interests: instead they had to make a stand on their own against exploitation, relying on their own resolve for withholding their labour power.

<return to top>

Self-Organising and Supporting Workers

Self-organisation, often supported by the IWA, and the Indian shop steward movement thus became a crucial part of the resistance of black workers to the experience of racial discrimination in the workplace. Although not a union itself, for many the IWA performed the role of one. The IWA supported workers in many industrial disputes over working conditions and discrimination from the 1960s onwards, the main ones in the West Midlands being at Coneygre and Newby foundries, Dartmouth Auto-Castings, Midland Motor Cylinder and Burnsall's. The IWA archive contains material on these and other national disputes involving Indian workers including the Imperial Typewriters and Grunwick strikes. At Midland Motor Cylinder the IWA campaigned against segregated toilet and washing facilities at the foundry. IWA members including Jouhl stormed the company’s Annual General Meeting at Llandudno to bring the issue to the attention of the management. As a result of this the facilities were desegregated.

As well as giving leadership and support in cases of industrial action involving Indians or in cases of racial discrimination, the Indian Workers Association assisted by raising funds for strikers, talking to members of the community, arranging meetings, leafleting, putting workers in touch with the TGWU and standing on the picket lines with strikers. During the strike against racial discrimination in selection for redundancy at Coneygre foundry, which was actively supported by the IWA, Joshi circulated a letter to all IWA members on behalf of the General executive Committee asking them to support the workers. The Association also supplied transport, placards and other logistical support to the strikers. Jouhl would take coal, coke and firewood to the gates of Coneygre in his minivan which was also used to provide shelter from the cold winter for the picket line. Other support came from the local community: gurdwaras provided food for strikers and demonstrators; landlords waived rent and grocers gave striking customers credit. With such collective action the struggles were not simply the struggles of workers for their rights but the struggles of whole communities for justice.

Despite the experience of racism, the IWA did not advocate the creation of unions solely for black workers since it was strongly felt that the struggle against working-class oppression could not be won if workers were divided along 'racial' lines. Nor did it abandon support for workers' struggles that were not specifically about 'race.' Support for the miners' strikes resulted in the IWA organising coaches from Birmid Industries to the Saltley Gate picket line, providing accommodation at the Shaheed Udham Singh Centre and in their own homes, and collecting funds. The IWA's role in organising industrial action in the Midlands meant that it had a significant effect on the mobilisation of black workers, particularly in the foundries, during the 1960s and '70s. In raising awareness of workplace racism, challenging discriminatory practices and championing the rights of black workers, the IWA achieved much in the way of social justice not only for the workers but also for their families and the wider community.

<return to top>

Direction for Learning

To further your knowledge on this subject you may wish to explore the activities of other black working-class organisations such as the Pakistani Workers Association, the Kashmiri Workers Union and the West Indian Workers Association which were active around the same time as the Indian Workers Association.

Many strikes involving black workers have taken place up and down the country from the 1960s onwards, from Red Scar Mill in Preston to the recent strike at Gate Gourmet at Heathrow. One way of exploring this history might be by creating a timeline of the important industrial struggles involving black workers in the Midlands. What connections can you make between these struggles?

<return to top>

Author: Sarah Dar

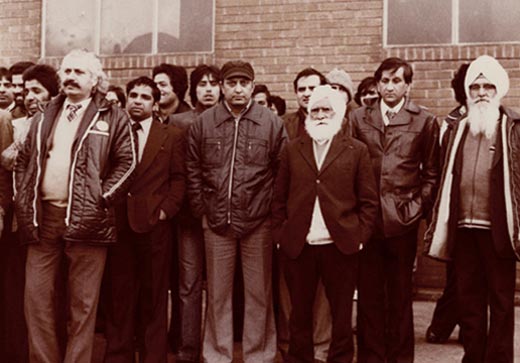

Image: Avtar Jouhl and Jagmohan Joshi, 1960s

[Birmingham City Archives: MS 2141/Digital Images]

|