Archives as Social Knowledge

by Dr. Bob Carter, Department of Sociology, University of Warwick

![]() Download this text in printable PDF format

Download this text in printable PDF format

Carolyn Steedman, the social historian, has provided the most apposite definition of an archive for the social researcher. She sees the material that constitutes an archive as empirical traces left by those who lived and died before us, and the archive itself as ‘a name for the many places in which the past (which does not now exist, but which once did actually happen; which cannot be retrieved, but which may be represented) has deposited some traces and fragments, usually in written form. In these archives someone (usually from about 1870 onwards) catalogued and indexed these traces’(Steedman 2001: 69). This definition identifies succinctly the properties of archives and indicates the key issues that these raise for the social researcher.

Archives, in the formal sense of collections of texts housed in a common place and catalogued for some purpose, have existed for a long time, but expanded significantly in the 19th century. This raises the important question of what gets left behind to be archived. Is this the result of deliberate decisions, and if so whose? If not, how do we assess the significance of what remains? And who decides that this material should be collected to form an archive? Archive institutions themselves, of course, require an infrastructure: a building to house the archive, sources of funding to provide for it, to pay the salaries of staff to catalogue and maintain it and to allow others to access it, and some sort of executive authority to authorise it. In short, archives require space, money and a degree of political stability. Unsurprisingly given these conditions, the development of the archive, in Western societies at least, is coincident with the rise of the modern state; indeed, in many cases the archive becomes a chief means of marking and emphasising state power (Steedman 2002).

It should be clear from this discussion that the materials found in an archive – the various sorts of texts that comprise it – ‘must be studied as social situated products’ (Scott 1990: 34). The interpretation of a text cannot be separated from the questions of its production and its effects. That is to say, in examining a text – a photograph, a play bill, a political pamphlet – we have to relate it to the intentions of its author(s) whilst recognising that its meanings go beyond these intentions and are not reducible to them. Moreover, all texts are produced with an audience in mind and so their interpretation has also to take this into account. These features of archival materials carry implications for the social researcher. First of all, archival materials cannot be regarded simply as ‘pure’ data awaiting sociological interpretation; as we have seen, the constitution of an archive is the outcome of a vast series decisions and accidents that invariably express the workings of social and political power. Second, sociologists bring a distinctive approach to issues of evidence and explanation which emphasises a particular orientation to archives. Another way of putting this is to distinguish between using documentary sources as topics (explaining the documents themselves) or as resources (an interest in what documents denote about the world).

Another aspect of archives as socially situated products is their materiality. Documents, posters, photographs and the like are not only forms of representation, but are also objects: written or typed onto certain sorts of paper, perhaps with an official crest or insignia; reproduced as part of a wider sequence in an album or a portfolio; framed and bordered, on cheap or expensive paper. This is not to reduce the content of the document itself to its material presence, but it is to suggest that their material characteristics have a significant impact on the way images are interpreted; different material forms both identify and shape different expectations and use patterns. In this learning package, for example, the experience of looking at documents on a computer screen will generate different understandings from those that might have occurred from the experience of looking at them in an archive room, among many other similar objects; looking at a photograph on the screen is likely to prompt different ‘readings’ from the same photograph viewed as part of an album. As Edwards and Hart argue, the ‘experience of the image component alone is not to be confounded with the experience of the meaningful object’ (Edwards and Hart 2004:3). And as we have already seen, the very materiality of the archive makes it vulnerable to the vagaries of political and administrative power.

Thus whilst archives can often reveal a ‘story’, be made to form a narrative, considerable caution has to be exercised in forming this story. Moreover, for the sociologist, as Goldthorpe has pointed out, a story is not a theory. The sociologist tends not to apply theory to history; rather she uses history to develop theory (Stinchcombe 1978) and archives are a key means of grounding theories of social change in historical analyses and evidence. This relationship is illustrated well in research using ethnography as a chief source of data generation.

Ethnography refers to the systematic description of the experience of a social group as this unfolds in its natural setting. Whilst participant observation – which involves the researcher participating in the activities of the group under study, either as a researcher or in some disguised role – is the predominant research technique used in ethnographic research, it is also the case that a full description of a group must also include an account of its activities and world view, especially as this is conveyed through its language, imagery and artefacts. In other words, an ethnographic description of a group cannot confine itself to the present; all groups have a history, are the products, however contingently or unintentionally, of earlier social forms and forces. To describe a group is to trace these by reconstituting, primarily from archives, the shared meanings that form the basis of the group’s solidarity and collective understanding. If we are to understand the present, then, we have to investigate the historical events and cultural contexts that are its sources.

Archives as Sociological Evidence.

However, using archives as sources of sociological evidence is not at all straightforward. There are two principal difficulties to be overcome, both arising from the nature of archives as human and historical products. First, as we have already hinted, an archive is a fragment whose survival and availability is vagarious. This raises serious questions about their quality as evidence. Second, all texts (not only those found in an archive) can be interpreted in many different ways, thus confronting the researcher with the problem of adjudicating between these interpretations. Furthermore, the relation of a document to the circumstances of its production – the intentions of its author(s), the potential audience, and its relations to other cultural conditions and so on – is often opaque. Using it to make claims about the meanings it may have held for contemporaneous social actors is therefore hazardous (this is equally the case with the obverse of this process, namely providing those in the past with motives and understandings derived from the present). Let us look at these two problems in more detail.

Scott (1990) has identified four criteria for assessing the quality of documentary evidence all of which apply to archive materials. These are:

a) authenticity: is the evidence genuine and of unquestionable origin?

b) credibility : is the evidence free from error and distortion?

c) representativeness: is the evidence typical of its kind and, if not, is the extent of its untypicality known?

d) meaning: is the evidence clear and comprehensible?

We will be applying these criteria to the archive sources in the package, but it should be made plain that the questions themselves often cannot be answered with much degree of completeness. They can, though, increase the confidence with which we can make certain sorts of claims based on them.

The second problem – that of interpretation and the meanings of texts – is more intractable (although it is not one confined to the analysis of archive materials). Texts, amongst other things, are forms of symbolic communication. That is to say, they first have to be encoded, in words and images, by their author(s) and secondly they have to be decoded by their audience. This dual process renders the meaning of texts indeterminate; texts cannot have an exact meaning because meaning does not rest in the text itself, but is the outcome of the interaction between the text and its audience. Since this will of necessity be symbolically mediated, a text will reveal distinct meanings depending on its audience and their purposes. This does not mean that a text can be interpreted in any way you like, since the text itself will constrain the sorts of interpretations brought to bear on it (you are unlikely to go far as a Shakespeare scholar by insisting on Hamlet’s comic possibilities), whilst ‘the Interpretive analysis (ethnography, case study, documents) must be based on a respect for this insight.

The key point, though, is that interpretation of archive materials is exactly that: the use of such interpretations as sociological evidence will be subject not only to Scott’s criteria but also to the recognition that interpretation can only be guided by reasonable

inference and historical knowledge; it must respect the insight of Herbert Blumer’s about ‘the obdurate character of the empirical world - its ability to talk back’ (Blumer cited in Lal 1990:89).

All of these properties of archives will be explored from the point of view of the social researcher in the learning package.

Interpreting and Measuring Evidence

An important type of historical knowledge that is required for the study of archival material consists of the conventions that we use to interpret symbols. Once we recognise an archive document as a form of symbolic communication, we need to consider the different ways in which it may be decoded or analysed. Thinking of archive material as complex texts provides a useful way of exploring the distinction between qualitative and quantitative analysis. Texts are made up symbols that are arranged in accordance with conventions. To the extent that we (the target audience) recognise both the symbols and the conventions that govern them, we may be able to reach agreement on the meaning of the text. We invariably bring a good deal of shared conventional knowledge to the process of interpretation, although this does not mean that people will agree on the meaning and significance of a document.

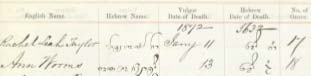

At the most basic level, the distinction between qualitative and quantitative analysis derives from the contrasting conventions that we associate with letters, words and numbers. Although we take the distinction between words and numbers for granted, this is nevertheless the product of a long history of human symbolic interaction, in which the abstract concept of "number" was transferred from number word to number symbol (Menninger, 1969). Qualitative analysis draws on a shared understanding of one or more human symbolic systems. When working with archives, more often than not the symbolic system is a written language. One example is the burial record in the Hebrew Congregation Register.

Obviously a knowledge of both English and Hebrew is required to interpret this record. Both English and Hebrew are alphabetic languages, i.e. languages in which written symbols (letters) have evolved to represent distinctive sounds. Complex sets of conventions underpin the combination of spoken symbols (recognisable sounds) and written symbols (letters) to form words, sentences and discourses in these languages. But a researcher would have to have learned both of these languages independently in order to interpret this document. Another important distinction is evident in this document: handwritten text and printed text. The invention of printing was associated with the rise of powerful new conventions governing the use of writing. While handwriting has its own conventions, these tend to be far less uniform. To understand this document it may also help to know something about nineteenth century handwriting conventions (did you recognise “Jany” as an abbreviation for January in the date of death column?).

Much archival research would involve this type of qualitative analysis, but are there records that would also lend themselves to quantitative analysis? The answer is yes, but this process is often very complicated to the extent that it involves attention to both qualitative and quantitative conventions. Quantitative research also involves shared interpretation, but here the common understanding is produced by manipulating the formal properties of numbers, which requires some understanding of the conventions used in mathematics and statistics. Numerical procedures can be applied to words as well, for example, by comparing the name and date of birth columns in the table presented above to determine a filial relationship between Rachel Taylor and another person in the register with the surname Taylor. The archetypal example of a record that can be used in complex quantitative reconstructions is the census return – an example of which is presented in this learning package.

Archives and Other Records

McCulloch (2004) has offered a useful distinction between official documents, institutional records and personal archives. Official documents are usually held in archives especially established for the purpose; institutional records (such as those kept by say a university or a political organisation) are often retained by the institution itself or else passed on to a local archive (the Indian Workers’ Association archive used in the learning package is an example of this); personal archives are often stored informally and may be difficult to locate or access.

The key to any archive is its catalogue, which should identify the documents held and provide some indication of its contents. The quality (or even the existence) of the catalogue is crucial to the researcher, but this will vary depending on what sort of archive is being examined. Although official archives often have the most detailed catalogues, in the UK they are subject to the Thirty Year Rule. This has been relaxed to some extent, whilst the Freedom of Information Act 2005 does give limited access to information held by public authorities, but access to public records in the UK is still very restricted compared to that of, for example, Sweden or Denmark.

These problems are not so marked with institutional records, where organisations have frequently taken steps to ensure that their records are preserved for the use of researchers. For example, the Modern Records Centre (MRC) at the University of Warwick holds, amongst other collections to do with labour history, the records of the Trades Union Congress. There are no restrictions on access for researchers.

Finally, mention should be made of other forms of printed literature and media some of which, such as censuses, newspapers, notices and minutes of meetings, diaries and letters, are used in the learning package. A good deal of what has already been said about issues of reliability, representativeness, meaning and authenticity applies to these forms of record, but there are besides some further points specific to them. In the case of diaries, letters and autobiographies (including memoirs), it is worth remembering that although these are often the most personal forms of record, they will nevertheless invariably take up public issues (see, for instance, the VJ Day diary in the learning package), sometimes providing a striking illustration of Mills’ (1959) claim that sociological understanding connects ‘private troubles’ with ‘public issues’. It might also be the case that these sorts of material present particular difficulties of analysis and interpretation: to the extent that they draw on personal and subjective experiences they are less susceptible of corroboration from other sources.

References

Edwards, E. and Hart, J. (eds.) (2004) Photographs Objects Histories: on the Materiality of Images London: Routledge.

Hammersley, M. (1992) What's Wrong With Ethnography? London: Routledge.

Lal, B. B. (1990) The Romance of Culture in an Urban Civilization: Robert E. Park on Race and Ethnic Relations in Cities London: Routledge.

McCulloch, G. (2004) Documentary Research in Education, History and the Social Sciences London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Mills, C.W. (1959) The Sociological Imagination Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Prosser, Jon ed. (1998) Image-Based Research: A Sourcebook for Qualitative Researchers London: Falmer Press.

Scott, J. (1990) A Matter of Record: Documentary Sources in Social Research Cambridge: Polity Press.

Steedman, C. (2001) Dust Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Steedman, C. (1998) ‘The space of memory: in an archive’ History of the Human Sciences 11(4): 65-83.

Stinchcombe, A. L. (1978) Constructing Social Theories New York: Academic Books