Introduction

The Operation of the Colour Bar

Responding to the Colour Bar

Directions for Further Learning

Introduction

The term 'colour bar' evokes the segregation of people on the basis of their 'race' as practiced in post-slavery United States and apartheid-era South Africa. During the 1950s and 60s however, it was common to hear talk of a colour bar in Britain - a term used to refer to racial segregation and discrimination. According to historians Sutcliffe and Smith (1974) an opinion poll of people in Birmingham conducted in 1956 found that nearly 74% thought there was a colour bar in the city. Although the British colour bar did not take the form of a government sanctioned system supported by a body of laws, it was a harsh reality and its effects had a negative impact upon many aspects of the lives of people, black and white, who had migrated to this country.

Despite being told stories about Britain by friends and relatives prior to migrating, many people found that the experience of racial discrimination was a matter about which they had remained silent. The harsh reality of prejudice and discrimination was thus something which migrants were generally unprepared for, as observed by Henry Archer:

"… where I was born in the West Indies we always look towards England as a mother country, you know, and we were never informed of all this discriminatory, all this discrimination that was actually taking place at that date. I didn’t expect such thing at all because most of the Europeans that were living in Trinidad and other parts of the West Indies, the people never discriminated against them, they always made welcome, you know, they live in the most posher residential areas so it was a tremendous shock to me really when I came and was subjected to that sort of treatment, you know, but nevertheless I have survived." [MS 2255/2/3 p8]

The challenges presented by the colour bar were disappointing and made some want to return home; yet many decided to stay and confront it.

<return to top>

The Operation of the Colour Bar

All aspects of life in Birmingham were affected by the colour bar from jobs, education, leisure and the provision of goods and services to the everyday attitudes of local people. One of the most significant areas in which the colour bar operated was housing. The deplorable living conditions that migrants were confronted with were largely the result of discriminatory housing policy and the operation of the colour bar in the private rented sector (see the pages on the Sparkbrook Association in 'Campaigns for Social Justice' for more discussion). One survey in the 1950s found that over 98% of people in Birmingham were unwilling to take on a 'coloured' lodger (Sutcliffe and Smith 1974). Since many migrants were refused accommodation on the basis of their ethnic background, multi-occupancy remained the only option for securing a roof over their heads:

"Well they said yes we could stay there for a time. I went upstairs, it was an attic room, and then I had a shock. Because I thought at the time it was a hospital. There were that many beds all in a row that… I had two cases in my hands and they both fell out my hands, I was shocked, and I said to my uncle, I said 'Come, let's go.' He held me back he said 'Where you gonna go?' he said 'We don't know anywhere.' So we stopped there the night, and the next day we went out and we saw notices rooms to let, boardings, bed and breakfast, things like that, and to every house that we went… as soon as the door was opened and they saw us, the door was slammed bang, they didn't wait for us to say a word. This was in Aston. And it was like that in all the places we went… You know you're not accepted after say the second or third day, after you've been refused accommodation then you know something is wrong." [The Colony MS 4000/6/1/37/1/C track 6]

Granville Lodge, who joined the RAF and came to England in 1944, highlights one of the typical excuses offered by people who did not want to take on a black tenant:

"… the lady or the landlady would say very seriously, “I am not prejudiced but my other tenants wouldn’t like it, so we can’t, you know, give you a room.” [MS 2255/2/85 p7]

As a result of this, on many occasions he had to sleep in doorways with his overcoat and some blankets wrapped around him.

It was common for Irish people to experience similar barriers in securing accommodation. Muriel Cowan explains how her aunts and uncles came over to Britain during the war but went back when it was over:

"I think it was the way they were treated like at that time because everything then was “No Irish need apply” and things like that you know and if they went to a door like it had vacancy up and they’d knock and ask for a room or something and the door would be slammed on them." [MS 2255/2/109 p16]

According to a local newspaper, when migrants tried to purchase property they faced differential treatment by estate agents and building societies (Birmingham Mail, 3/10/1963). Mortgages and loans were offered at less favourable rates to migrants than to white buyers and were refused on properties in areas where black people were found to be concentrated.

Evidence of the colour bar could also be found in hotels, public houses and clubs across the city and surrounding areas. Prior to 1965 racial discrimination in Britain was not illegal however, the campaigning efforts of many individuals and organisations were to force legislative change. Correspondence in the Indian Workers Association archive reveals typical disputes over racial discrimination in pubs where black people were commonly refused service, forbidden entrance to certain rooms and even threatened by staff on the basis of their skin colour. Newspaper articles focusing on the issue of the colour bar, for example the case of the daughter of a Jewish councillor who was refused membership of a tennis club, and a youth club in Smethwick which banned 'coloured' members can be found in the archive material of the Indian Workers Association [MS 2141/A/7/2].

<return to top>

Responding to the Colour Bar

The experience of racial discrimination led migrants to develop strategies to provide security and support for themselves in an unfamiliar land. Their responses were sometimes spontaneous and creative but above all they demonstrated the adaptability and resourcefulness that individuals and communities employed in order to survive in Britain. Their responses also demonstrated that a growing sense of community was essential to their eventual settlement.

The Pardner system, a form of banking which has been used by African-Caribbean communities across the world, was one system imported from the Caribbean which was used by migrants to raise funds for house deposits during the 1950s and 60s. Friends, family and close acquaintances contributed a set amount of money on a regular basis into a central fund and each person took their turn in withdrawing their 'hand'.

Networks were an important resource that migrants could draw on for support. Those who lacked accommodation were able to acquire a place to stay or work through contacts which were already in the country, like Jacob Prince:

"… my first accommodation then was I went to the Wolverhampton New Road, there was a bit camp there which like call it hotel….not a hotel, it was a hostel and there there was a few of the ex-RAF lads there and the situation was “boy, I’ve got nowhere to live, all I have is a suitcase.” “well, no problem, you can stay with me until there is a vacant.” So what we used to do we used to use the canteen, pay for our meal, at night squat into one of the lad’s hut, one of the lad’s chalet until there is a vacant applying and that’s what it was all about… in other words, we used to help each other…we had to help each other…" [MS 2255/2/96 p6]

Granville Lodge explains how in the 1940s Caribbean airmen adopted a safety in numbers approach against the threat of racial attacks:

"… walking down the street in the blackout dark and some British airmen, and other airmen, especially Americans, if you’re by yourself, they would attack you and beat you up, so if you’re walking down and you see a face that is black, “hello there” and they would come over and walk with you, as a matter of well, security and there’s a lot of… terrific bondage between the British… between Jamaican, not necessarily Jamaican, West Indian airmen and for security reasons, for safety reasons." [MS 2255/2/85 p6]

The development of social and political organisations and other support structures gradually provided the support that migrants needed in order to establish themselves in Birmingham and the country as a whole. These structures developed by migrant communities will be explored in more detail in Laying the Foundations.

<return to top>

Directions for Further Learning

Fighting the colour bar was an important past of social justice campaigns both regionally and nationally which you can read more about in Campaigns for Social Justice.

What are the similarities and differences between the ways colour bars have operated in Britain, the United States and South Africa?

<return to top>

Author: Sarah Dar

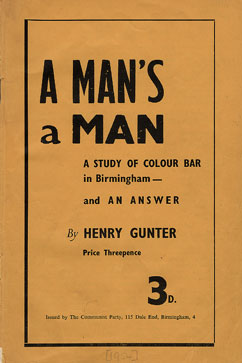

Main Image: Cover of A Man's A Man by Henry Gunter, 1954

[Social Sciences]

<return to top>

|